|

My father sat in the cardiologist’s waiting room as the nurse took my mom back for a stress test. It would be awhile. Dad thumbed through magazines and people-watched to pass the time.

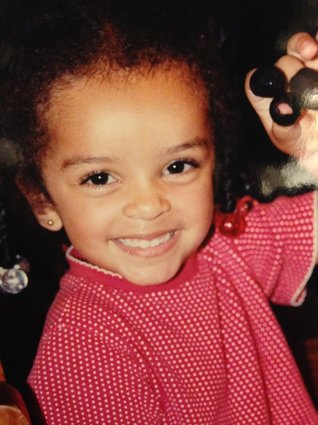

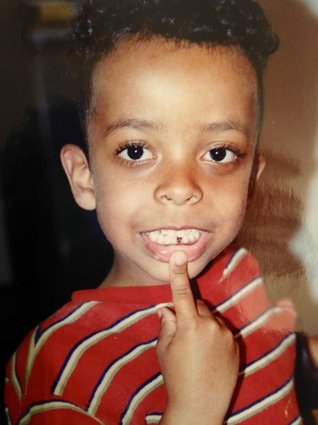

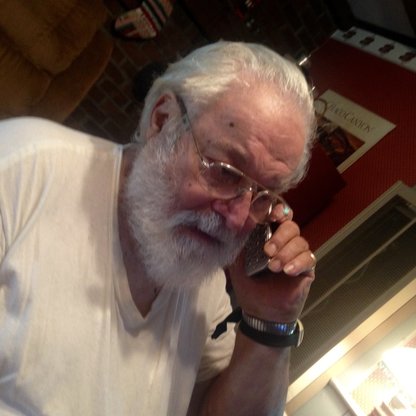

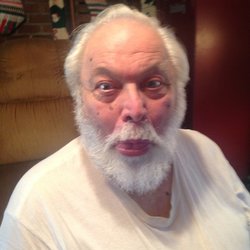

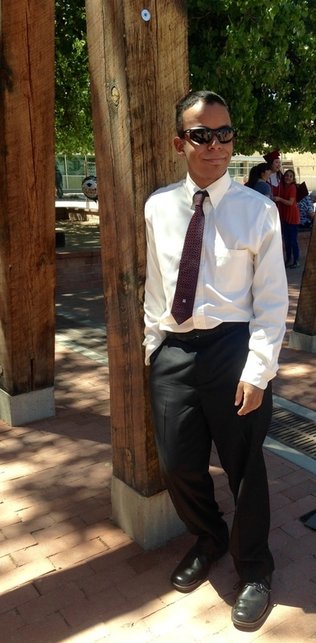

“Mr. Revels,” called the nurse. Dad looked up when he heard the name. Revels, he thought. An older Black gentleman stood to follow the nurse. My father watched him cross the room and wondered if he could be related to my husband. Revels was not a common name. This was upstate NY, and I Iived 2000 miles west in Albuquerque. There couldn’t possibly be a connection, he mused. But he waited, and watched the door for Mr. Revels. Dad was Italian, and growing up Italian in the 1930s and 40s meant that like many other first generation immigrants trying to assimilate, there were challenges. If your last name carried a vowel at the end, you were closed out of some circles of society. The dark-skinned Sicilians especially were targets of mistrust and contempt. In the south, they were sometimes listed as “black” on census forms, and some became victims of lynching. As they vied for social mobility in direct competition with those in the Black community, schisms formed between the two cultures and Italians worked to distinguish themselves from their rivals. My dad tried to teach his children to do the same. He taught me his tricks. His fears. His angst. His wheeling, dealing way of bargaining through life. I grew up hearing the Italian words that communicated contempt for Black people. When my sister dated a mixed-race young man in high school, Dad bit his lip. “She’ll grow out of it,” he said. When I started dating Black men in college, Dad disallowed my youngest sister from attending the same university out of concern for my influence on her. “I don’t want another daughter dating tsootsoons”. But time and contact with my circle of friends began showing my father a new way to connect with Black people. He slowly started to disengage from the assumptions of his past. It was a feat then for him, years later, to say yes to my husband Scott, who is Black, and Scott’s request for permission to marry me. My father was adding to his repertoire of tools for engaging the world. Dad watched the door for Mr. Revels to emerge, hoping it would happen before my mom was done. His mind ticked off the questions he might ask this man, if he had the chance. The door opened. “Excuse me,” said Dad. He stood and approached the gentleman. “Did I hear your name was Revels?” “Yes,” said the man. Dad said he had a puzzled look on his face as Dad came near. “My daughter married a Revels. Scott Revels. They live in New Mexico. Do you happen to be of any relation to Scott?” “Scottie? In Albuquerque? ” said the man. “Yes! That’s Jim’s son! With his other two boys, John and Jim! And daughter, Andrea. Yes those are my cousin's children!” “Wow,” said Dad. “He’s my daughter’s husband. This is unbelievable. What a small world we live in. I’m Vinnie Parlato. So nice to meet you.” He held out his hand in greeting. “Nice to meet you,” said the gentleman. His look of puzzlement bloomed into a smile as he took my father's hand. “I’m Thomas Revels. So Scottie is your son-in-law?” They traded details about their lives and this odd discovery of having a familial connection with a total stranger. They lived a mere 30 miles apart. Dad pulled out his wallet and together they stood in the waiting room flipping through photos of my son and daughter - children that they were both related to by blood. “This is my grandson, Cole. And my granddaughter Gianina,” said Dad. “Scottie’s children,” said Thomas, shaking his head. “Wow. Those are Scottie’s children.” Dad called me immediately upon returning home that afternoon, excited to tell me about this chance encounter. He had reached a point in life where he was beginning to recognize God’s hand in orchestrating such strange occurrences. I was fascinated to hear him reiterate this story, and felt my heart skip a beat or two. You could hear the smile in his voice and his wonder at the impossibility of such a confluence of circumstances. I imagined them standing there, these two older men who had never met before - one Black, one White - as they perused pictures of two small children, their shared kin. It warmed me to know that my father carried around the photos of my son and daughter, and shared them with pride that they were his grandchildren. His brown grandchildren, whom he loved. The “old dog”. He had learned some new tricks. What a different man than the one I grew up with. Neither he nor I could have imagined this was even possible, fifty years ago. “No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.” ― Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom

12 Comments

|

Susan Parlato RevelsArchives

June 2024

Categories

All

links to other sites

www.abuacademy.com

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed