|

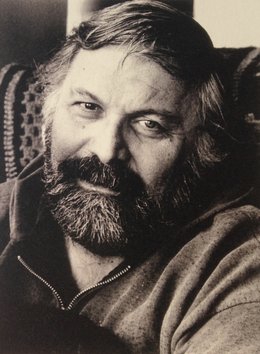

For the day of his funeral, July 14, 2017 – by Susan Parlato Revels

“Vinnie,” I heard my mom say, “Susan is not breathing any better.” From under the towel with my head over a bowl of steaming water, I listened to my parents, Vinnie and Barb Parlato, discuss my condition. “I think I need to take her into the hospital,” said Dad. Once again, my lungs were the seat of some infection that constricted the bronchi. This time, the midnight steaming didn’t break up the phlegm. At 12 years old, on a bitter night in the dead of March, the only thing I wanted was to crawl back into my warm bed. Instead, I was bundled in a parka and into the truck, nightgown and all, and Dad and I headed out into the darkness. It was one of those nights where the sky was cloudless and any heat the earth had gathered from the day was shunted off into space. It left the air crisp to the resistant membranes of my lungs. My fevered body withdrew deeper into the parka. The truck rumbled along to the sound of the tires muffled on snow packed pavement, and my wheezing. We wound through deserted streets and came to a stop at Oneida City Hospital on Main. I followed my dad through the astringent air towards the entrance. What I didn’t know was how that air was causing a break up of mucus in my chest. As we walked through the doors into the vacant reception room, some congested plug deep in my lungs broke loose and completely blocked the passages. All breathing ceased. I dropped to the floor. Without air flow, I couldn’t shout out to tell my father something was wrong. I watched as Dad walked toward the nurse at the reception desk, unaware of the emergency unfolding behind him. How could I get his attention? I flattened my palms and began smacking them against the tiles, hoping he would hear the slaps. The nurse pointed at me. “Your daughter! Your daughter!” Dad turned to see me, and ran. He scooped me up and carried me down a hallway, busting through the doors into the emergency unit. “My daughter can’t breathe,” he screamed. Staff whisked me into an exam room pulling off my parka and beating my back. Up onto an exam table. Lights. Shouting. Beating. Faces. Hands. One nurse had just pulled off my night gown when suddenly, the beating loosened the plug and with one wretching movement I vomited a great volume of green mucus into the hands of the nurse standing in front of me right into my nightgown. I looked with consternation at what had just exited my lungs. “Wow,” I thought. “I am sick.” I could breathe again, with strident whistles. They admitted me that night and put me in an oxygen tent. A tracheotomy tray stood at the ready if needed. Dad saw me settled in. He went home. I went to sleep. Years later, reflecting on that whole incident, I never thought I would die, nor was I afraid. Why would I be. Everything would be okay because, my Dad was there. I remember being small and carried in the muscled arms of my father. The world looked different at 6’3”. We crawled on his broad back when he’d lay on the floor to read the funny papers which sometimes descended into tickles and laughter. On occasion, we’d watch fleas jump across the outspread paper. “Barbara! We have to bomb the living room!” The animals would all get new flea collars. Dad always found extra work to supplement his day job as in industrial arts teacher at Canastota High School. There was Ackerman Construction in the summers. Carl’s Drug Store at night. From our beds, we’d hear him return home from his night job. Did he bring ice cream this time? He’d come to the bottom of the stairs and shout, “WHO WANTS A MILKSHAKE?!” Five voices shouted, “I do!” and ten feet would stampede down the stairs. In his forties he decided to learn the horseshoeing trade, and that was his second job for the next 15 years. Music often filled the house on Lake Road. When Clair de Lune was played, Dad would sit for the length of it with eyes closed. Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, The Glenn Miller Orchestra were regular fare. Mom and Dad would dance in synchrony around the family room. As a child, I’d stand on his construction boot toes and have him whirl me around in a fox trot. As I grew older, I learned the steps myself, and how to follow his lead. On summer mornings when teenagers want to sleep in, Dad would stand at the bottom of the stairs and yell, “Everybody up! We have work to do!” No stampede to these words. Weeding the very large garden with 90 tomato plants alone. Canning and freezing vegetables. Grooming horses. Cleaning the barn. During hay bailing season, my brother would drive the tractor. Two sisters would be up on the hay wagon. I wanted to be with my father, walking alongside and throwing bales up to my sisters, hayseed weaseling down inside my overalls. At the end of a long day, he’d plop down in his arm chair and put up his feet. “Can you pull my boots off please?” One of us would bend to untie his boots. Once the second one came off he’d reach out to try to touch us with his sweaty toes, laughing. “Ew Dad, Ewwww!” Seasons came and went. The leaves changing color - always a time of wonder for my father. And when geese filled the skies for their southern migration, Dad would shout, “Geese! The geese are flying!” and we’d pour out the door to stand, watch, and listen with him. Life threw its share of wrenches into the works. Jamie, my baby brother, died. My mom got sick. Our family was in trauma and as a teenager, for the first time I saw my father cry. When he leaned over to rest his head on my shoulder and weep, I felt inadequate. How could I, one so insignificant compared to this mountain of a man, be strong enough to support him in his need? I wished I could have been bigger for him. Time brought the children leaving Lake Road bound for college or the military. One winter I returned for an 8-month period while seeking my next job opportunity. After work, while sitting in the sunroom reading, I’d feel the room shake as Dad made his way to sit in a chair near me, just to talk. This became a pattern between us for many months. I eventually found a job that would take me far away, to New Mexico. I could hear the dread in his voice as the day for my departure drew near. That day, he helped me pack my life into a car to drive 2000 miles across the country, alone. “I want you to call me, every night, when you’ve gotten into a motel.” “It’ll have to be collect calls, Dad.” “I don’t care. Call me. Every night.” He hugged and kissed me goodbye, then walked back into the house choking back tears. He couldn’t watch me drive away. But their visits to New Mexico brought adventure. Their first time out I didn’t know what my parents would do just hanging around my house, so I planned a road trip. How would it be traveling in the car with them for 7 whole days? But the first day out, a half hour into the journey, Dad said, “Geez every time you turn a corner here, there’s something new to look at!” His appreciation for the grandeur of nature became more and more apparent to me. We found potsherds at Chaco Canyon and went camping in the Kaibab Forest of the Grand Canyon. Sitting around the evening campfire surrounded by darkened forests, he kept the machete close at hand. “I don’t know about this,” he said smiling. “I feel naked without my gun.” Over the years, we would talk of God and the future. “Look Dad. Isaiah says that God will create a new heavens and a new earth, and they will be so spectacular, we won’t even remember the old ones. Can you imagine? And Dad. Isaiah says, ‘They shall build houses, and inhabit them, they shall plant vineyards, and eat the fruit of them. They shall long enjoy the work of their hands.’ Dad, we’ll be working with our hands in heaven, planting, and eating the harvest.” He listened. He resisted scripture at first. But as years went by, and life became more burdensome, Dad began to see God’s hand more clearly. A cane became a walker. A walker became a wheelchair. He began to see God everywhere. At first, it was in the parking lot at Walmart. “Sooz, I’ll be driving up to Walmart praying about how I’m gonna get in the door. And when I drive up, a handicapped parking spot opens, or someone’s coming out with a scooter!” “Yeah Dad. Isn’t that amazing? And remember, God is more than just a parking lot god. He wants you to trust him with the big things, as well as your parking space.” Dad began to speak to God outright and acknowledge Him day to day. He turned to contemplate his life, and eventually came to recognize all along where God had stepped in to set a different course. He saw that nowhere more so than when as a young soldier, he was on his way to Korea, and Providence intervened to change his deployment to Japan instead, and he survived the war. As his days grew difficult, he would call on Jesus to help him stand to his walker. “Help me Jesus. Help me Jesus.” Watching my father decline in strength and ability was grueling to witness. But hearing his whispered pleas to Jesus gave me that peace that goes beyond all understanding. My father could be opinionated and stubborn, as well as loving and loyal. But he instilled in us, his children, a fierce work ethic, and galloping independence. A respect for higher education, and an appreciation of nature. We are all highly opinionated, stubborn, loving and loyal….in our own ways. Although, we do get rid of a lot more things than he did. Job, the most ancient book in the Bible, is about a man who lived well before the Law was given to Moses. Job knew that God was his Redeemer. He was tested beyond strength, yet in his testing he said, “For I know that my Redeemer lives and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth. And though after my skin, worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh - shall I see God: Whom I shall see for myself, and mine eyes shall behold, and not another.” Job believed in the resurrection, and when God returned to stand upon this earth, Job would be there, in his very flesh, to see God with his own eyes. My father will be there too. And so will I. Until then, Clair de Lune will always move me to tears, and hearing the mournful call of geese flying overhead will stop me in my tracks. One day, I will see my Father again. But he will be different. No gray hair. No weakened muscles. He will no longer have need a of a walker. And he will run. He will run to me and whirl me around in his arms and say, “Sooz I’ve missed you!” and then show me around Paradise. We will dig rows in the soil and cover over the seeds with our hands. And I’m sure, we will each reach for a sun-kissed tomato from his 90 tomato plants, pull them fresh from the vine, rub them against our shirts, and bite into their sweet warm flesh, again and again, and again. My name is Susan Parlato Revels, Vincent’s daughter. Thank you for coming out to remember my father today. Thank you for listening to my stories. At the reception, I hope to hear some of yours.

5 Comments

|

Susan Parlato RevelsArchives

June 2024

Categories

All

links to other sites

www.abuacademy.com

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed